Preservation Oklahoma is pleased to announce the 2022 list of Oklahoma’s Most Endangered Places. POK aims to promote the places where Oklahoma history lives by bringing awareness to historic landmarks across the state. POK seeks nominations from the public in October every year and a team of historic preservation professionals meet to decide what properties to include on the list. Although inclusion on the list does not guarantee protection or funding, recognition for these structures may increase restoration efforts and possibly ensure their longevity. A variety of property types were nominated from across the state. The 2022 list features a mix of commercial, religious, and educational sites ranging from pre-statehood to mid-century.

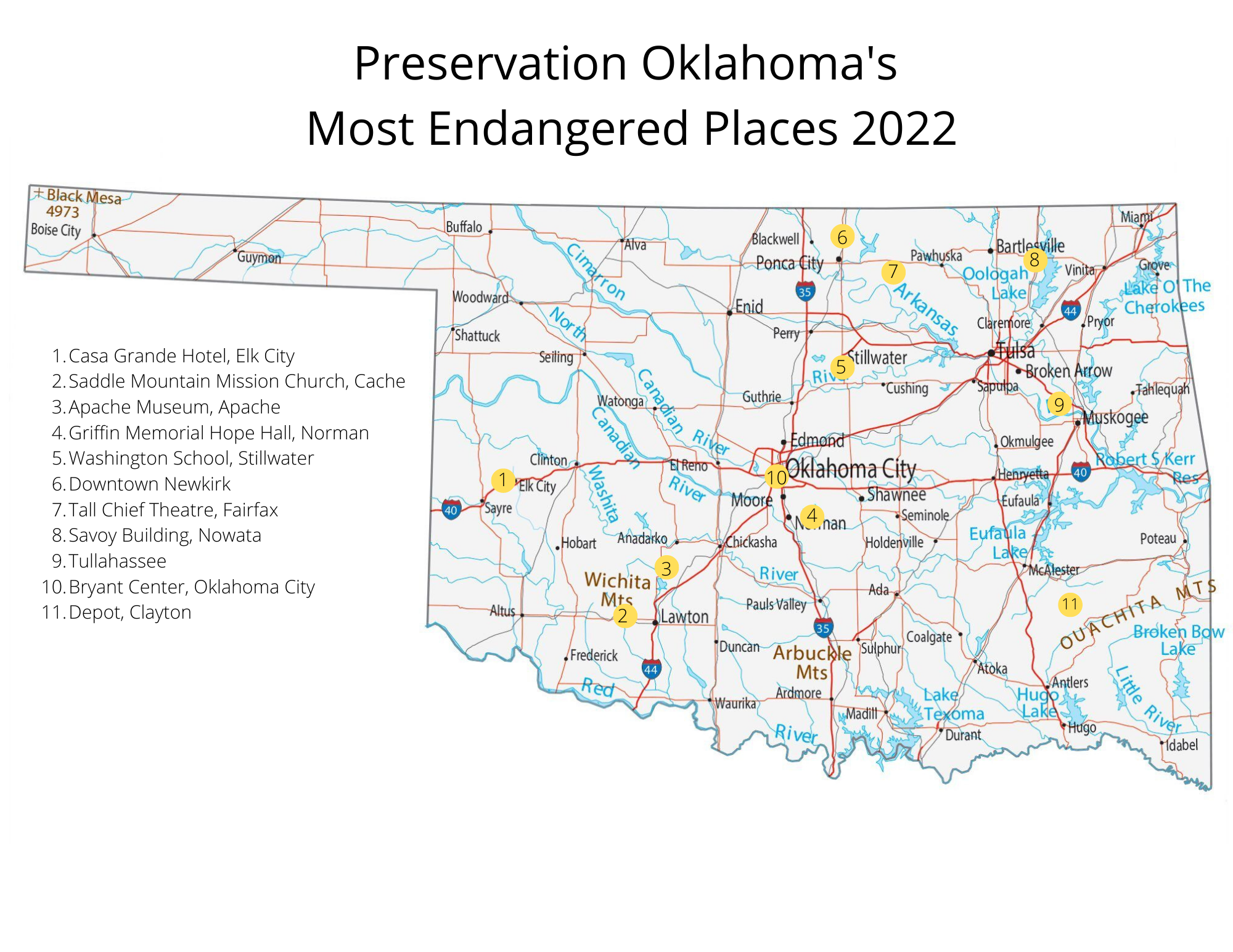

The 2022 list of Oklahoma’s Most Endangered Places include:

Casa Grande Hotel, Elk City

An icon of downtown Elk City for over 90 years, this four- story, Spanish Eclectic style hotel was constructed in 1928 utilizing the design of the Oklahoma City firm of Hawk and Parr. Located on Route 66, it is the largest hotel directly on the route between Oklahoma City and Amarillo. It represents the high-water mark of first-class hotels along the route. Soon, this type of hotel was supplanted by the tourist court and the motel. Casa Grande was the site of the 1931 U.S. “66” Association’s National Convention. It most recently served as a geology/oil and gas museum. Vandals and time have taken their toll on the building. It is in need of a new roof and tighter security. Casa Grande was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1995.

Casa Grande Hotel, Elk City. Photo: Chantry Banks, POK

Apache Museum, Apache

Constructed in 1902, this stone commercial building occupies a prominent corner in the town center. It helps define a picturesque intersection. It combines elements of two popular Victorian era styles, Romanesque and Queen Anne. The heavy, quarry faced stone walls are pierced with round arch fenestration and a typical canted entry. Above the entry is the corner turret, sheathed in pressed tin and capped with a conical roof. It currently is the home of the Apache Historical Society Museum. The north wall and area around the entry have both failed, and repairs have begun, but there is currently not enough funding to complete the project. The historical society has reached around 60% of their fundraising goal. The building was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.

Apache Museum, Apache. Photo: Chantry Banks, POK

Saddle Mountain Mission Church, Cache

On April 9, 1896, a thirty-one-year-old Baptist missionary from Canada named Isabel Crawford arrived at Saddle Mountain to establish a Baptist mission station. The congregation built and paid for a chapel that it dedicated in 1903. The mission was also the site of a large (and still active) cemetery. Clashes with Baptist officals eventually led to Crawford’s forced transfer from Oklahoma in 1906. At her death in 1961 her body was returned to Oklahoma and buried in Saddle Mountain cemetery. The church was notable for the number of Kiowa missionaries and pastors it produced, including George Hunt, Ioleta McElhaney, and Sherman Chaddlesone. In 1963 the building was moved to a privately held amusement park called Eagle Park. It sits here today, alongside Quanah Parker’s Star House. Both properties are in very poor condition. Action is being taken with Star House, and there are hopes to do the same with the chapel.

Saddle Mountain Mission Church, Cache. Photo: Abandoned Atlas

Griffin Memorial Hope Hall, Norman

Construction began in 1928 on Hope Hall at what was then called Central State Hospital. It was expanded and remodeled several times over the years. Originally used as a men’s receiving ward, it also was home to a women’s receiving ward, and later, a home for veterans experiencing PTSD and other mental health issues. As long-term mental health care became less of a priority, the need for a building of this size diminished. Hope Hall closed its doors in 2012. The future of the building is unknown. Griffin Memorial Hospital still operates on the grounds and the area is heavily monitored.

Hope Hall, Norman. Photo: Abandoned Atlas

Booker T. Washington School, Stillwater

African American and Afro-Indigenous people were among the earliest settlers in Indian Territory. In the first half of the 20th century there were more than fifty Black schools located throughout the state; most have already been demolished or lost. Booker T. Washington High School is one of the only three remaining examples and is the only one available for potential acquisition for preservation and interpretation. The building has been vacant and falling into disrepair for more than two decades, yet recent surveys show it to be in reasonably sound condition. It is prone to flooding, which largely accounts for its survival (the property has not been sold, so it remains standing). Increased awareness of this structure, its significance and the history it represents are crucial in telling the complete history of the state of Oklahoma.

Black history is underrepresented in the built landscape of Oklahoma. Buildings prominently associated with this history are less likely to have survived, either through re-development, demolition, or neglect. Architectural surveys have determined eligibility for National Register of Historic Places status. No nomination has yet been made because the building is owned by a private development firm; yet there is openness to preserving the building. Greater awareness of its importance to the community and national significance are needed. It is among the only remaining structures documenting the history of Black Stillwater.

Washington School, Stillwater. Photo: Abandoned Atlas

Downtown Newkirk

Newkirk, the county seat of Kay County, was platted in 1893 and white settlers arrived in September of that year when the Cherokee Outlet was opened. By 1901 the downtown area had twenty imposing stone structures, most of them built of native limestone quarried east of the community.

The Newkirk Central Business District is a three-block area that includes the majority of the historic commercial development in the area. The district is comprised of one- and two-story structures, dating from 1894 to 1920. Most buildings are in the Romanesque Revival, Commercial, and Colonial Revival styles. It has been an Oklahoma Main Street Community since 1992 and was the first small town to receive the Oklahoma Main Street Award.

While many of the buildings remain structurally sound, the Mason Stanley Building is on the verge of collapse. The front façade is buckling between the first and second floors (a turnbuckle has not been maintained). Maintaining the integrity of the district is of the utmost importance.

In 1984 the Newkirk Central Business District was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Downtown Newkirk. Photo: Alyssa McCleery

Tall Chief Theatre, Fairfax

Built in 1928 as both a Vaudeville and movie pictures theatre, the Tall Chief is a beautiful reminder of the not-so-distant past, when weekend plans were determined by what was on the marquee. While unassuming on the outside, the Tall Chief has a grand interior and seats 800 (half the population of the community).

Alex Tall Chief, father of world class ballerinas Maria and Marjorie Tallchief, built the theatre. At one point the Fairfax Police station was housed in a tiny office in the front. This was during the time of the story of Killers of the Flower Moon. A shoot out in front of the building left one of the murderers dead in the street while children were watching a Western inside! It last saw service as a theatre in 1960.

In 2017, a tornado ripped through Fairfax and did considerable damage to the roof. Help is needed to secure the interior from further deterioration.

Tall Chief Theatre, Fairfax. Photo: Carol Conner

Savoy Hotel, Nowata

The Savoy, constructed in 1909 on the town square, was a three-story, brick building where oil leases were signed and formal balls were held. The elegant hotel boasted sixty-two rooms, a telegraph office, billiards, and dining room. In 1915, radium water was discovered from a well drilled in town. The Savoy became a bathhouse where travelers would come, hoping to heal rheumatism, stomach trouble, malaria, nervous trouble, and skin diseases. In later years the building also served as a county hospital.

The building has been bought, sold, and renovated many times over the last century. With a decline in population and tourism, the hotel was abandoned in early 2000s. Another renovation commenced in 2009. A new roof was being installed when a worker fell to his death. Since then, no work has been done and the building is deteriorating.

Savoy Hotel, Nowata. Photo: Abandoned Atlas

Tullahassee

Tullahassee is considered the oldest of the surviving All-Black towns of Indian Territory. Tullahassee is one of more than fifty All-Black towns of Oklahoma and one of thirteen still existing. The town was incorporated in 1902 and platted in 1907.

In 1916 the African Methodist Episcopal Church established Flipper Davis College, the only private institution for African Americans in the state, at Tullahassee. The college, which occupied the old Tullahassee Mission, closed after the end of the 1935 session. The A. J. Mason Building was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. The Carter G. Woodson School is listed in the Oklahoma Landmarks Inventory as a resource related to African American history.

Today, around 100 residents call Tullahassee home. Not much remains of the original town, but it is important to recognize its history and contributions to the state.

Tallahassee. Photo, Abandoned Atlas

Bryant Center, Oklahoma City

Built in 1960, The Bryant Center was a hub for Oklahoma City’s most prominent Black community. After sitting dilapidated for many years, its owner is pushing for the building to be granted historical significance and preserved from demolition.

Once housing a bowling alley, a restaurant and a dining club at its peak, what was formerly known as The Bryant Recreational Center has fallen into a state of disuse since the 1980s.

Over the years, despite the owner’s best efforts, the former entertainment center has been grounds for trash dumping and homeless encampments. Graffiti covers much of the building as well.

The goal is to preserve the building for the benefit of the community. A new roof is needed but the walls are in decent condition.

Bryant Center, Oklahoma City. Photo: Abandoned Atlas

Frisco Depot, Clayton

Clayton is in the Kiamichi Valley in Pushmataha County and is situated at the junction of U.S. Highway 271 and State Highway 2. The town was initially called Dexter, and a post office was established on March 31, 1894. The post office name was changed to Clayton on April 5, 1907. The St. Louis and San Francisco Railway had built a line through the Choctaw Nation from north to south in 1886–87, with Dexter/Clayton developing as a lumber mill town along the route from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to the Red River.

The Frisco Depot was built in 1889 and is one of the few remnants from the town’s heyday as a lumber mill town. Almost all original features remain, although the shake roof was replaced with shingles at some point. The depot is eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. It appears to be in stable condition, but continued exposure to the elements will make preservation difficult.

Frisco Depot, Clayton. Photo: Matthew Pearce, SHPO

Established as one of Preservation Oklahoma’s first programs, Oklahoma’s Most Endangered Historic Places was patterned after a similar annual list produced by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Ralph McCalmont, one of the founding board members of Preservation Oklahoma, had also served on the board of the National Trust and was keenly aware of the program’s impact. Realizing the need for Preservation Oklahoma to focus public attention on the state’s historic structures, the Board of Directors agreed to publish an annual list of “properties and sites which have special historic or architectural significance to our state, but which are in danger of being lost, due to neglect, poor maintenance, obsolescence or other causes.” The purpose of producing this listed was stated by John Mabrey, then the President of Preservation Oklahoma, when he said “if we bring the problems to light of a structure familiar to people, they are more likely to do something about it.”

Over the past twenty years, people have done “something about it.” While inclusion on the list does not guarantee protection or funding, it has proven to be a key component in mobilizing support for the preservation of historic sites by raising each structure’s awareness to a statewide level. The nomination process has evolved to reflect the fact that the public is aware of the need to preserve their local structures. Today, nominations are solicited annually from the public. The nominations are compiled and the formal list is selected by a group of preservation experts, including historians, architects, and archaeologists.